Where does the music go?

(post from the series My Way of Composing – click to see the complete series)

Well, let’s assume then that a process of reflection has already set in motion the fundamental ideas for the composition that is to come. This is what I call being in composition mode, that is, staying in a flow of thoughts and explorations about the sound you want to shape. You feel that everything is in motion, and even when you go to take a shower or go out to buy food, you are still ruminating on ideas. Above all, you are itching to create music. This is the unmistakable signal to start getting hands-on. But how do you actually begin composing?

Here, it’s important to consider a determining ontological factor for music: time. If you are drawing, creating a website, sculpting, or even organizing your home or something, you have your object in front of you all the time. When you change something (say, when you add a stroke or move a piece of furniture in the room), you do so with an immediate awareness of the entirety of your art. With music, as with other time-based arts (like a film, for example), it’s not quite like that. What you add isn’t in front of you, it’s behind you. To use conventional concepts of time, it can be said that musical composition deals with the past (memory) or the future (expectation), and not with the present (except in a figurative sense, but that would be another matter). You cannot have an entire piece of music in front of you, right? It only exists as something that unfolds over time.

From a compositional perspective, the only way to see music as a whole is through prospection, that is, future-oriented thinking. You imagine what will happen and establish how it starts, how it develops, and how it ends. This is what we call pre-compositional planning. Some people are very detailed in pre-composition, establishing groups of notes to be used (which in musical terms we call modes), instrumentation, number of sections, and even their durations. Depending on the level of detail, one might even need to resort to visual or mathematical resources to plan, making charts, calculating proportions between sections, etc. Planning becomes very necessary, for example, when you are creating music for an existing video, as in the case of a film scene soundtrack. But, generally, the level of detail in pre-compositional planning varies according to the personality of the composer.

I am one of those who prefer to work from already composed sounds, that is, with little detail in pre-compositional planning. To put it bluntly, I don’t usually draw up charts nor think about where the music will go before I start creating it, but these factors can vary with each project. A possible disadvantage of vague planning is the (not good) feeling of being lost during the creative process, that is, feeling that the music being produced does not align with the reflections that set it in motion, or that we do not know where we are heading. The great advantage of composing with little planning is the ability to create atop the sounds you have already invented, and not those you anticipate inventing. You don’t need to be an acoustics expert to know that sound is an extremely complex phenomenon. Pre-compositional planning, no matter how detailed, can never fully account for this complexity. If you plan in great detail, you naturally try to implement this plan during the creation of sounds, and this effort can make you “deaf” to various sonic and conceptual possibilities that arise along the way and had not been anticipated at all. Ultimately, I believe this issue is not about planning everything or not planning at all, but always something in between these two extremes. Even though I’m not an expert pre-compositional planner, I always carry my notebook, where I record and sketch ideas during the compositional process, and this too is a form of planning.

Let’s then move to the two examples of my compositions and their planning. As I mentioned in the introduction to this series of posts about my compositional process, my examples are not recipes for anyone, nor will I embellish my methods, painting myself as a genius who extracts his music from the heart in a passionate act of writing. No. I will be quite frank and try not to fail in sincerity, pointing out even the things I did by accident.

Composing “Eternidade à deriva”

It is a piece for chamber orchestra, older, from my undergraduate days. The professor said: create a piece based on literature. After spending some time lost in various readings, I chose these verses by Luís Miguel Nava:

The stone, I say, falls into the belly

of the water like a fist

– now it lies at the bottom of that image

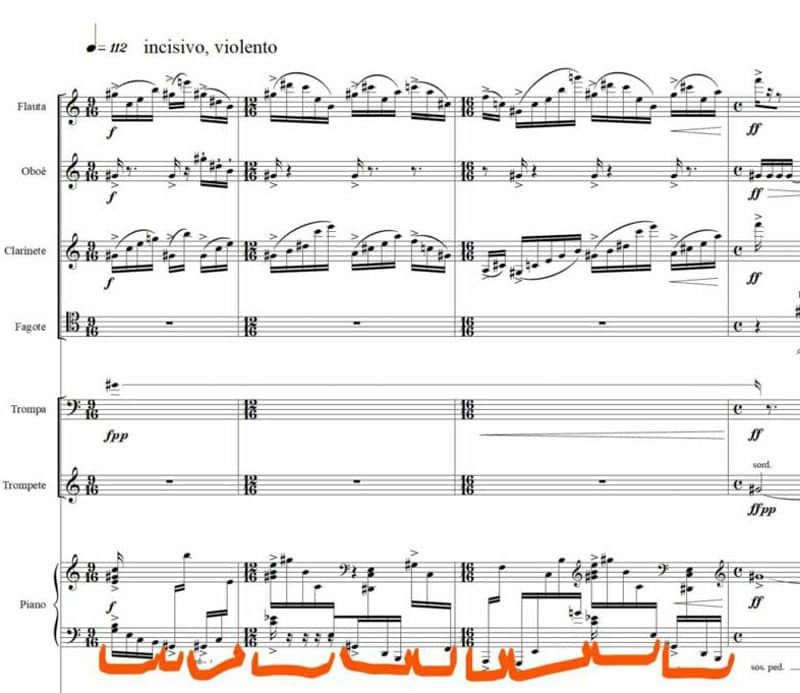

My idea was to represent the impact of the stone hitting the water through music. For this, I planned to start with a burst that, over time, would subside. The image I had in mind was the surface of a lake. The impact of the stone on the water would be the beginning of the composition, raw and full of movement. Gradually, the waves generated would become weaker until the lake returned to its original state. With this definition, I planned the impact that is in the first bars of the piece, and this planning was quite strict: (Step 1) I sat at the piano and devised a sequence of chords with a sound that seemed harsh to me, with marked dissonances and notes spread across the bass, middle, and treble registers. (Step 2) I decided beforehand to arpeggiate these chords with rapid and constant speed, giving a mechanized and impassive air to this opening. (Step 3) I also decided to break the regularity in the succession of chords: instead of doing everything in groups of four, I chose to alternate between groups of 2, 3, 4, and 5 notes (hence I had to use these odd time signatures in the score). In this way, the chord changes become unpredictable, which adds greater intensity to the chaos of this beginning.

This beginning, and the subsequent gradual cooling of the music (always in accordance with the image of the lake), was all I planned before I started composing. I didn’t know how it would continue or end, nor what would happen when the waters of the lake returned to their initial state. The sequence of the composition happened like this: when I reached the ‘calm waters,’ so to speak, I decided to create a section with the string section, which until then had been underutilized. And along the way, the idea to insert a quotation from a famous melody by the French composer Olivier Messiaen occurred to me. It’s from the beginning of his piece Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus (Praise to the Eternity of Jesus), the fifth movement of the Quatuor Pour la Fin du Temps (Quartet for the End of Time). This melody, originally played on the cello, is extremely slow, with piano accompaniment in chords that repeat periodically. Listening to it, we get a very strong impression of this idea of eternity, which Messiaen, as a devout Catholic, associated with Jesus Christ. If you haven’t heard it yet, grab your best headphones and listen for yourself, as it’s worth it:

This quotation, which appears at the end of the string section in my piece, would become essential for the remainder of the music and, more importantly, for the overall concept of the work. The title itself, “Eternity Adrift,” emerged from this. This shows that the absence of prior planning about the end of the piece left a path open during the composition process, which ultimately was imagined along the way, through a series of associations made between the music that had already been composed, Nava’s poem, and things that appeared along the way, like Messiaen’s composition and his idea of eternity. I like this sensation of joining things through musical composition, when you compose and associate texts, ideas, videos, and events, all unplanned. In a way, when this happens, I feel that I am on the right track, as the composition truly appears to me as something alive and interactive.

My idea for the ending came after introducing the Messiaen quote: unlike what happens in the cited piece, I decided to alter the timing between the piano chords. With this shift, the idea of eternal stability was dynamized, and then I began to introduce the other instruments, which fill and intensify the texture of the strings. This flawed eternity, which ultimately moves and is also subject to time, is what made me add ‘Adrift’ to the title, as an indicator of our inability to achieve the eternal, that is, to overcome Time – I confess that these thoughts were also influenced by Book XI of Saint Augustine’s Confessions, which, in the wake of Messiaen, I started to read at that time. The music ends by moving again, reaching a climactic point and grounding itself in Messiaen’s initial chord, but finally sinking and fading forever, and here the image brought by Nava’s last verse becomes notable, that of the stone at the bottom of the water. Will it be forever?

The experiments in “Passagio – String Quartet No. 2”

Imagine that you have just been given the opportunity to write a piece of music for a group you are a huge fan of. They have already committed to playing your piece, you just need to create and send it. What a chance, right? And at the same time: what a responsibility! This is what happened to me when the Campos do Jordão Winter Festival commissioned me to write a string quartet, to be performed by the Quatuor Diotima. I have been following the work of this quartet for years, listening to them on the radio and through various recordings available on the internet. This was a piece that required a lot of preparation, as I was really afraid of not meeting the expectations of the occasion – both my own and those of others involved. I listened to and analyzed kilos of music for string quartet, jotting down information about techniques and notations that seemed interesting. However, when it came to thinking about the music, planning what it would be like and what it would contain, I couldn’t get started. Above all, having the opportunity to write a piece for such an excellent group, I wanted to include everything I could imagine in the piece, in an experimentation without limits.

After many ideas started and abandoned, I decided to throw caution to the wind. I tossed the planning aside and simply began to write music, straight from bar one and moving forward in order. I had no idea what would come next; it’s like starting to write a story without having a story, although this is more common than one might think in the literary world. You write an opening sentence, something like

John woke up without an appetite, but made coffee anyway, continually haunted by flashes of memory from the previous night.

But in reality, you still have no idea who this João is, nor what might have happened the previous night. That’s more or less how I started the music, and this attitude continued from the beginning to the end of the work. I would compose a section, let its energy grow and reach somewhere. Then I would stop and think: what could happen now? Occasionally, an interesting idea would emerge, and I would implement it, and so on. To say that I didn’t plan anything at all wouldn’t be true, I should mention that from the start I determined that, given my exploratory, clueless approach in this piece, I had to ensure that the flow of music was constant, that is, that one thing always transformed into another, without cuts – this was crucial to avoid ending up with a piece that seems like an incongruent patchwork of smaller pieces.

This was not the first time I made music this way, but it was certainly the most risky. When you connect two things in life, you need to balance them, give them coherence, and respect their energy. In that story of João waking up, for example, we could introduce a Maria in the following sentence. However, if we did that, we couldn’t then abandon Maria. We would have to give meaning and importance to her presence in the story, she would need to take actions, interact with João. And all this would have to be tied in some way to the progression of the story.

As more things are added to the story, this need grows exponentially. That’s why it wouldn’t be accurate to say that I composed Passagio without planning, because with every new step taken, I needed to reconcile everything that had happened before, and therefore I was forced to think about what would happen later, even though I remained committed to always transforming the music. To this day, I’m not fully convinced that this equation was effective. At times, I think the piece is a whirlwind of actions not always coherent; at other times, I am pleased with this elusive music, which never finishes establishing itself anywhere and ends up going away. If you wish, draw your own conclusions:

In the next post, the question that will guide us is: What is music made with?

Learn or Order from Bruno Angelo

A real composer to work with you.